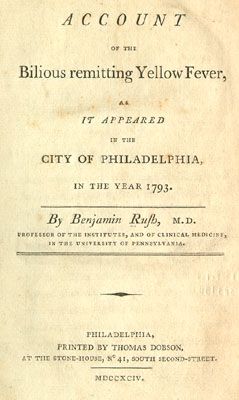

In the third installment of our limited series, we discuss the outbreak of Yellow Fever, which ravaged Philadelphia in the year 1793, along with the various treatments for this particularly terrible plague. We also discuss the manner in which the very new American Government handled the situation, how mercury and Vicks vapour rub got involved, along with a smattering of Hamilton references.

Listen on Buzzsprout here!

In 1793, Philadelphia held a special place in the newly formed United States. Only 10 years past the Revolutionary War, the city was acting as a temporary center of the government during the construction of the new capital building in Washington. Adding to its importance was the port, surrounded by seven blocks where most of the occupied homes were located.

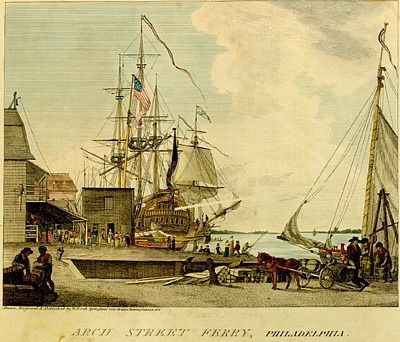

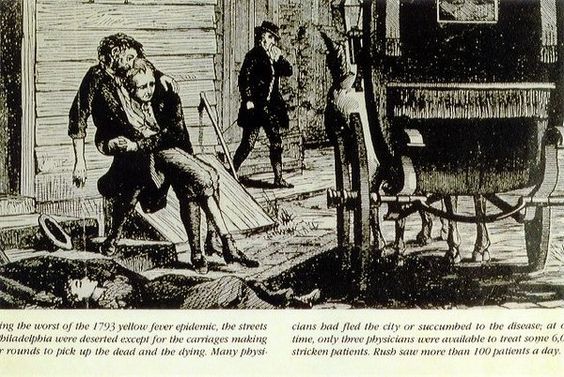

In late spring, merchant ships came into port, fleeing a slave uprising in northern Saint Dominique (now known as Haiti). Donated by a wealthy Philadelphian named Steven Girard to assist in relocation, they carried 1400 French refugees and 600 enslaved persons. Reports indicate that passengers began showing symptoms of illness en route, and their arrival in the densely-packed housing districts only spread the contagion.

Yellow Fever is a virus that is thought to have originated in West Africa. It spread to the Caribbean and North America via the slave trade on ships owned by Dutch and American companies. Mosquitos, the vectors of the disease, were able to cross the ocean on these ships and were causing outbreaks in Barbados and Guadalupe by the mid-1600s. Certainly by 1793, symptoms were familiar enough to be recognized by those who had encountered it before.

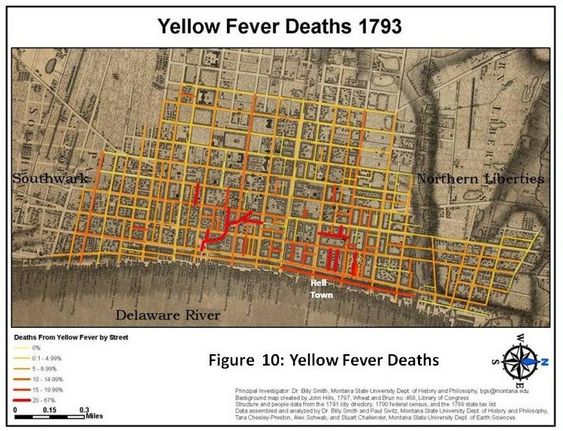

Once the mosquitos aboard Girard’s ships came ashore, they were able to breed quickly in the standing water in the streets, as well as outhouses built close to wells. Because mosquitos travel only about a quarter of a mile during their lifetimes, the initial spread of the disease took time, with each generation of the bugs expanding their territory a little further during their two-weeks on earth.

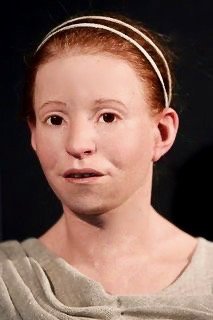

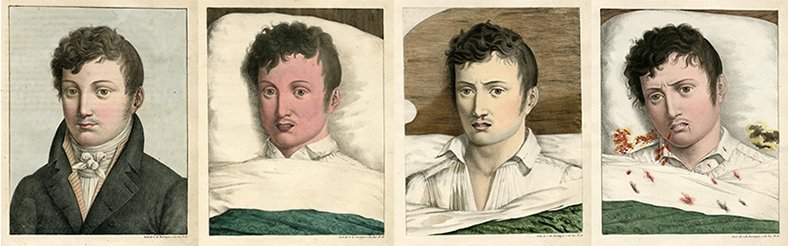

In both 1793 and modern outbreaks, Yellow Fever is characterized by rapid development of a high fever, flushed face, nausea, joint and muscle pain, fatigue, and an infection of the upper eyelid. After initial onset, the fever will relent, only to return a few days later with yellowing of the skin known as jaundice (caused by damage to the liver) that gives the virus its name. As tissue damage continues, the gums and gastrointestinal tract will bleed, leading to vomiting of black blood, shock, and death. In modern cases where patients develop jaundice, the death rate is between 20 and 50%.

As the death count rose, Stephen Girard felt responsibility for the outbreak, as he had provided the ships that carried the contagion. He threw himself into efforts to care for the sick, establishing a care center at Bush Hill and personally performing the duties of a nurse at the peak of the epidemic.

Other city leaders and doctors had more creative approaches to stopping the spread. Suggestions ranged from avoiding night air (probably effective as mosquitos are nocturnal) to exploding caches of gunpowder in the streets to improve the air quality (less effective but more entertaining). See our episode for a lively and full discussion of various remedies, as well as which 18th century cures we would opt for! Spoiler: early heroic medicine was given a hard pass by each of your hosts.

Three months after it began, the disease relented as the chilly fall air killed off the mosquitos. The city slowly relaxed, and government officials began to trickle back into the city. Alexander Hamilton had never left, and contracted and survived the fever. George Washington, who had avoided the disease by leaving town, refused to return until the first good hard frost.

Yellow Fever would return to Philadelphia in the coming years, but never with the terrible impact of its 1793 rampage. It would take 145 years until a vaccine would be available, but since its debut in 1938, only 12 post-vaccination cases have been identified. The vaccine appears to provide lifelong immunity, so the WHO recommends vaccinating infants between 9 and 12 months in areas where the fever occurs frequently (mainly the tropics). Though Yellow Fever continues to take lives each year, it is no longer an unstoppable force.