Our second foray into the world of lost Russian royalty, in which Allison provides tea-pouring ASMR, Jillian takes us on a journey to the past, and Hannah betrays her true feelings for Nicholas Romanov’s soulful eyes.

Listen on Buzzsprout here!

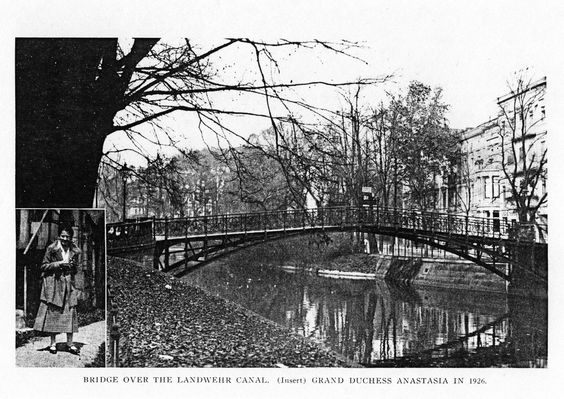

On February 27th, 1920, a woman was rescued from a Berlin canal after jumping from the Bendlerbrücke bridge. She arrived at the hospital with no papers and could not provide her name, so she was admitted as Fräulein Unbekannt: “Miss Unknown”.

Two years after her arrival, a fellow patient told tell a Russian émigré named Nicholas von Schwabe that she had shared a hospital with Tatiana Romanov. Intrigued, von Schwabe visited Miss Unknown and became convinced she was the Tsar’s daughter. At his request, Miss Unknown began to receive an increasing number of visitors.

Baroness Sophie, a former lady-in-waiting to Tsarina Alexandra, gave her opinion on the identity of Miss Unknown: she was too short to be the willowy and statuesque Tatiana. Miss Unknown replied, “I never said I was Tatiana.”

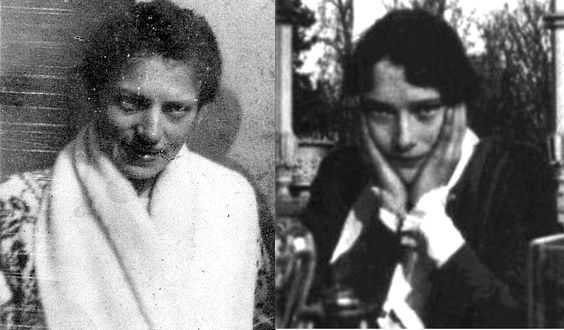

Within months, Miss Unknown had a growing following who believed her to be Anastasia. She moved into the home of a former Russian Poland police chief named Arthur von Kleist and began referring to herself as Anna (short for Anastasia) Tschaikovsky.

Meanwhile, a German police officer named Franz Grünberg was determined to get to the bottom of the claims. He arranged for her to stay at his estate and invited several members of the European aristocracy to identify Anna, including Tsarina Alexandra’s sister, Princess Irene. While Anna refused to see her, other visitors did manage to meet her in the coming years, including the Imperial family’s former tutor Pierre Gilliard and Tsar Nicholas’ sister Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna. None confirmed her as Anastasia.

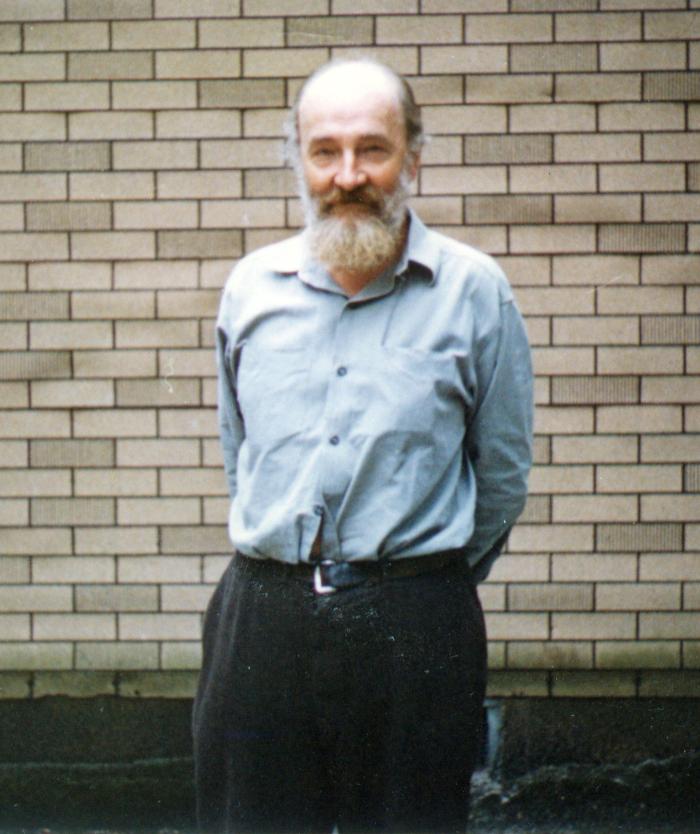

During the next few years, Anna spent time in hospitals and sanitoriums, funded by Anastasia’s great uncle, Prince Valdemar of Denmark. And when we say hospitals and sanitoriums, this is what we mean:

During her time at Oberstdorf, Anna received a visit that would mark a turning point in her life. Tatiana Melnik was the daughter of the Romanov’s physician, Eugene Botkin, who had remained with them after the Revolution and accompanied them in Ekaterinburg. Tatiana threw her support behind Anna, saying that her memory had been damaged by mental illness and providing her with details of the Romanov family and court life.

Around this time, Prince Valdemar stopped supporting Anna due to pressure from his family. Fortunately, funding came from another distant relative of the Romanovs, and Anna was transferred to Castle Seeon in Bavaria.

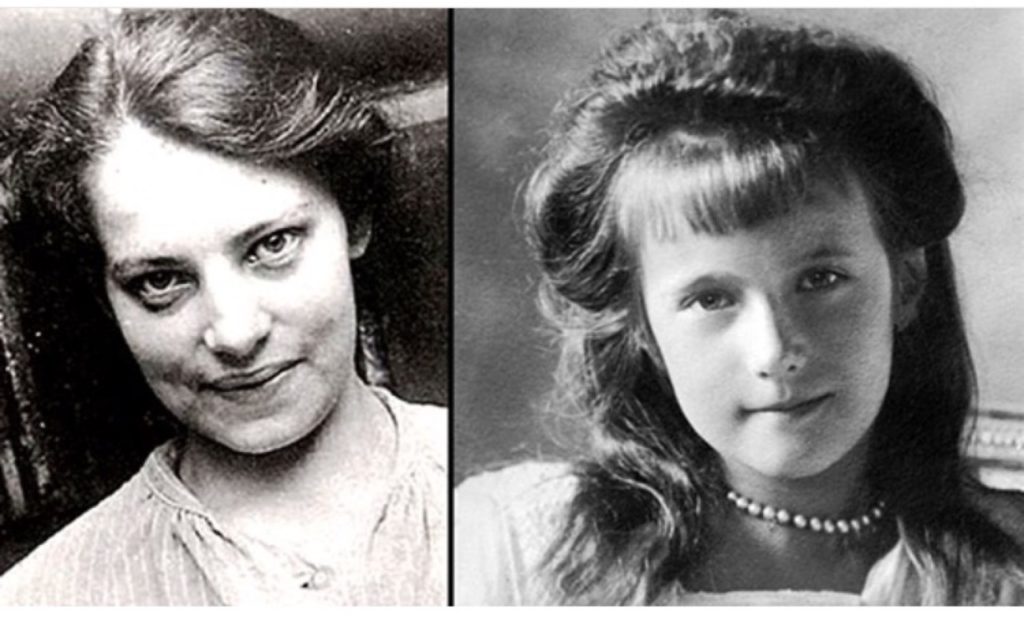

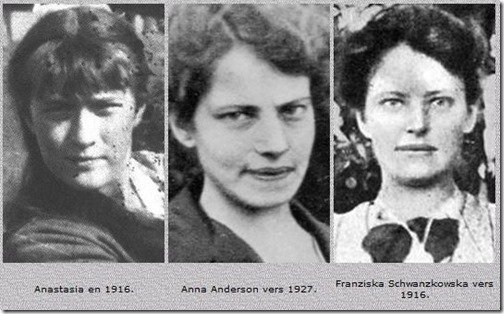

By 1927, Anastasia’s extended family was running out of patience and wanted answers. Tsarina Alexandra’s brother Ernest, Grand Duke of Hesse, hired a detective to investigate. Within a short time, he returned with information: Anna Tschaikovsky was actually a Polish woman named Franziska Schanzkowska. She had been involved in a tragic accident at the munitions factory where she was employed, inadvertently dropping a grenade which had exploded, injuring her and killing a fellow worker. This caused a break in her mental health, and she had been committed to two asylums prior to going missing in Berlin.

To confirm this new identity, the detective arranged for a meeting between Anna and Felix, Franziska Schanzkowska’s brother. Felix appeared to recognize his sister, but when the time came to sign the official documents, he would not give absolute confirmation. Later, he would state that he knew it was his sister, but lied in order to give her a better life.

Meanwhile, debate continued to rage amongst the royals of Europe. Felix Yusopov, nephew of Tsar Nicholas and one of the conspirators who killed Rasputin, wrote a scathing letter denouncing her claims.

On the other side of the spectrum, Eugene Botkin’s son Gleb was fully on Anna’s side. He and another supporter arranged for Anna’s journey to America, where he hired a lawyer to set up a company with the goal of getting hold of Anastasia’s inheritance. This angered many of the relatives of the Romanovs, who believed Gleb was acting out of a desire for financial gain. Upon the death of Nicholas’s mother, who had never given up the belief that her son had survived, the closest remaining relations signed a document declaring their belief that Anna was an imposter. Gleb responded with an accusation that they were after financial gain.

Anna’s life in America continued. For a while, she was the toast of New York society, but that came to a halt as her mental health broke down once more. After spending time in the Four Winds Sanitorium, she was sent back to Germany, where she lived in yet another psychiatric home. Upon her release, she was given housing by various supporters. At the time, the Nazi government had an interest in determining whether they had a former member of the Russian royal family on their hands, so they arranged one more meeting between Anna and the Schanzkowskas. However, upon being told that Anna would be imprisoned if discovered to be a fraud, the family refused to sign any affidavits against her.

Anna settled in a house on the borders of the Black Forest, but sadly, mental illness struck again. She eventually had to be removed from her home, which was in disrepair and filled with 60 cats. At this point, she took Gleb Botkin up on his offer of financing her return to America.

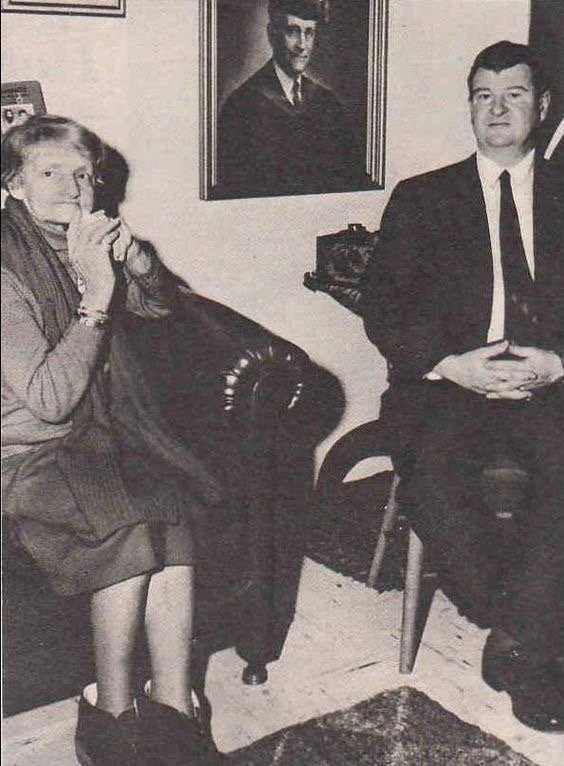

Anna moved to Charlottesville, Virginia and married history professor John Eacott Manahan, a friend of Gleb’s with a deep interest in Russian history. Though it was probably motivated by necessity (it took place just before Anna’s visa expired), John loved the thought of being married to a lost Grand Duchess and called himself the “Grand-Duke-in-waiting”. On the whole, this slightly strange marriage seems to have been a happy one.

Anna faced a number of health problems in her twilight years, at one point requiring the removal of a tumor and portions of her intestine (bookmark that!) She was placed in a nursing home in 1983, but was quickly “rescued” by her husband, who took her on a Bonnie-and-Clyde style tour of the Virginia countryside fueled by convenience store snacks.

After a brief stint on the run, Anna was returned to her care facility, where she passed away on February 12th, 1984. Her body was cremated; some of the ashes were interred at Castle Seeon and some with her husband after his death in 1990. Her claims, however, did not die with her. Join us next time for the conclusion to our three-part series, where we will discuss answers to the mysteries surrounding Anna and the Romanov family.

*This claim has no historical basis whatsoever.

Leave a Reply