In this final episode of our three-part investigation and discussion of Anna Anderson, we discuss the true fate of the Romanov family, along with our affinity for Yul Brenner, and how we truly feel about Don Bluth’s adaptation of this story.

Listen on Buzzsprout here!

When we last left the Romanov family, they were incarcerated in a house in the remote Russian town of Ekaterinburg. Accompanying them were their faithful retinue: Eugene Botkin, the family’s doctor, Anna Demidova, lady-in-waiting, Ivan Kharitonov, cook, and Alexei Trupp, footman.

After 78 days of captivity, Dr. Botkin was awoken around midnight on July 17th and told to gather the family and servants: they were about to be moved. They dressed and were escorted to a small cellar in the basement, which was decorated with striped wallpaper and lit by a single bulb. Here, they were told they would wait for a vehicle to arrive.

The family was arranged as if they were posing for a picture, with Alexei and Alexandra seated. When they were in position, Yurovsky informed Nicholas that due to continued efforts of his relatives to rescue them, the family was going to be executed. A confused Nicholas asked, “What?” and Yurovsky repeated himself, then shot him in the head.

The guards opened fire, but disorganization and the confined space made the rest of the killings a drawn-out ordeal. To add to the horror, the guards’ bullets were bouncing off the girls’ corsets, which were lined with diamonds and precious stones: the family’s financial cushion in case they were able to escape. Yurovsky and his men resorted to rifle butts and bayonets to finish the job.

After 30 minutes, the bodies of the whole family and their retinue lay still. Yurovsky checked the pulses of each one to make sure they were dead. However, as the bodies were being shifted onto sheets to be carried to a truck in the courtyard, one of the girls (either Maria or Anastasia) sat up, covered her face with her hands, and screamed. She was quickly set upon by the guards and killed.

Now came the task of disposing of eleven bodies. The bodies were loaded into a Fiat truck (the only one in town, which had arrived hours late.)

The truck was driven outside the city on a forest road to the Four Brothers Mine. After being stripped, the bodied were dumped down a mineshaft. However, it wasn’t deep enough to hide them, so they were pulled out and driven back down the road.

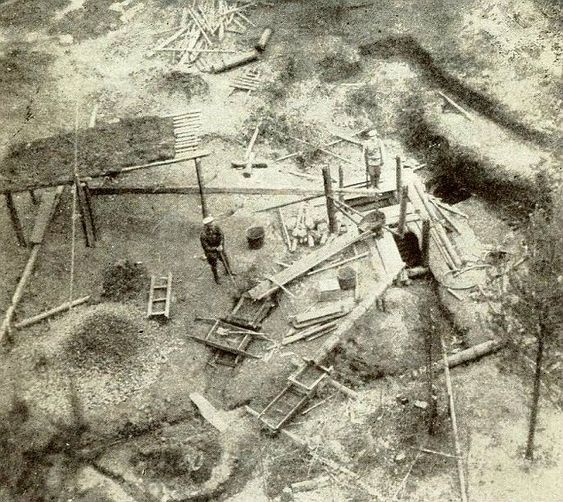

When the truck stalled out in the middle of the road, Yurovsky decided complete the burial right there. He ordered his men to dig a shallow grave and throw the bodies in. In an attempt to confuse anyone who came looking for eleven bodies, Yurovsky pulled two of the corpses from the grave, burned them, and buried them separately 50 yards away. Returning to the main grave, he and his men poured sulphuric acid over the remains, covered them with soil, and laid railroad ties over the top, backing over them repeatedly to drive them into the mud and disguise what was hidden below.

The bodies would remain hidden for more than sixty years. However, the hiding place wasn’t a complete secret. A few people, either those who were involved in the killings or high in the Soviet ranks did know about the railroad ties on Koptyaki Road. In 1928, a poet named Vladimir Mayakovsky asked an official to visit the site and wrote a poem about the experience called “The Emperor”.

Past Iset –

the mines and cliffs

Past Iset –

the whistling wind,

at verst Number Nine

the ispolkom driver

stopped, stood,

silent…

Here is a cedar,

axed over and over,

notches straight through the bark.

By the root of the cedar

a highway

and in it an Emperor –

buried.

In the mid-70’s, a local geologist named Dr. Alexander Avdonin began investigating the location of the remains. Using local legend and clues from those who were in the know (such as Mayakovsky’s poem), he was able to find the main gravesite in May of 1979. Avdonin kept the discovery under wraps for a long time out of fear of the Soviet government, but in 1991, nine sets of remains were exhumed from the main gravesite.

The next step was to determine whether the remains were in fact the Romanovs. The bullets and sulphuric acid containers found in the grave pointed to Ipatiev House, but they weren’t absolute proof. However, after craniofacial analysis, age assessment, and DNA testing performed by scientists from several different countries, it was confirmed: Nicholas, Alexandra, Tatiana, Olga, and another daughter (either Maria or Anastasia) had been found.

All the remains were reinterred in 1998 at St. Petersburg Cathedral. But two spots were left open for the children who were still missing: Alexei and his sister. Then finally, in 2007, an amateur search group found bones in a clearing of birch trees. The search was over. Alexei and his sister were accounted for.

Today, the last two sets of Romanov remains are being housed in a research facility waiting to be interred with the family and retinue. The former gravesites on Old Koptyaki Road are marked with Orthodox crosses, and there is a cathedral on the site of the demolished Ipatiev House,

In the second half of our episode, Allison took us on an amazing journey through media inspired by Anastasia (the real one and the fictional ones!) We discussed the road that led to the Don Bluth movie we all know and love, beginning in 1956 with a star-studded film!

In the mid 90’s, Don Bluth and Gary Goldman signed a deal with 20th Century Fox for a new animated feature. Fox wanted to adapt a property they already owned, and Anastasia was the chosen one. With Angela Lansbury, a singing bat, and Allison’s pick for Greatest Villain Song of the Mid-90’s, it’s not one to miss!

More recently, a Broadway musical opened based on the animated movie. The plot is more down-to-earth (i.e. no more singing bats) but we have it on good authority that it’s still worth the watch. This plot features Gleb, a Bolshevik general assigned to kill Anastasia, in place of our favorite dancing wizard.

One bright spot to leave on: when the White Army entered Ekaterinburg shortly after the murders, they found a survivor from Ipatiev House: Alexei’s spaniel, Joy. Joy was taken to England and lived out the rest of his days as well-cared for dog, even being reunited with Sophie Buxhoeveden, who he greeted by ” leaping in the air and running to [her] with his forepaws, walking upright like a circus dog”.