In the first episode of our limited series on the plagues of the past, we dive into the plague of Athens. In a lively discussion led by Allison, we talk about how the Athenians and their neighboring city-states handled the epidemic, some unique funeral practices, as well as Allison’s collection of death plushies. We also talk about DNA and, of course, our beloved troll person Andrew Lloyd Webber.

Listen on Buzzsprout here!

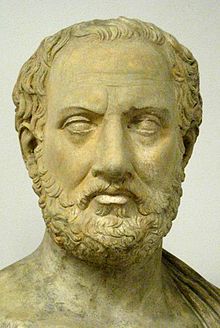

In order to learn about the plague of Athens, we turn to someone who had first-hand experience with the events: Thucydides. In addition to being a great sculpture model, he also not only lived through and chronicledthe plague of Athens, but contracted and SURVIVED it. He also had a longstanding rivalry with fellow historian Herodotus (click here for the full story courtesy of Kate Beaton!)

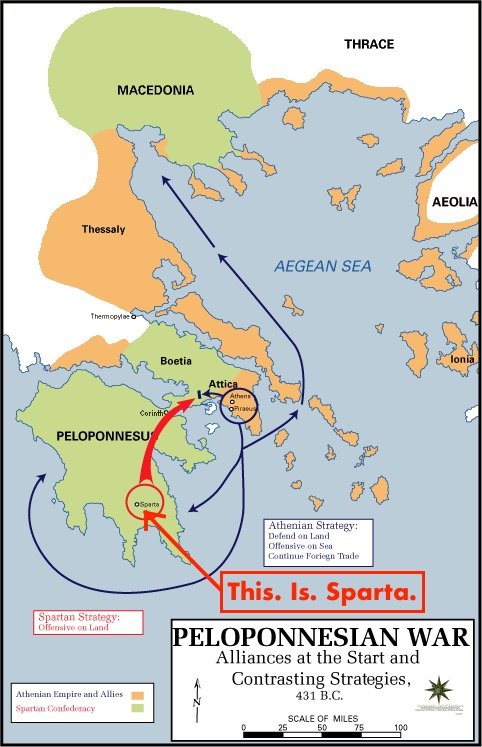

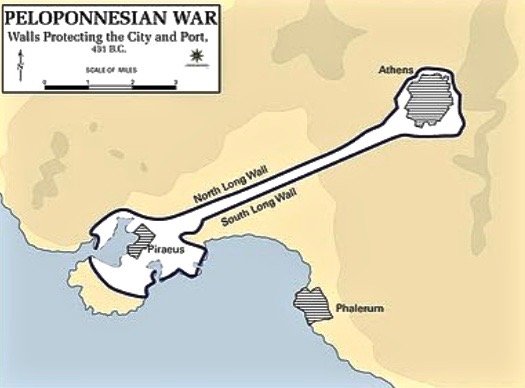

Our story begins about 2,400 years ago in the Greek Isles. After the Persian empire had left the area, Sparta and Athens were left in a fight for dominance. Sparta took the land war approach, trying to blockade Athens and starve them out.

In response, Athens built an encompassing wall about 3 3/4 miles long to provide a safe connection to their port city even under siege. The rural population also moved inside the walls for safety, which is said to have tripled the combined population of the two cities.

Into this dangerous combination of a port city with crowded conditions came the plague. Seemingly healthy individuals would be stricken with coughing fits and other respiratory symptoms, inability to sleep, dry heaving, skin breakouts similar to pimples or ulcers, and a strange feeling of heat of the inner body (though patients were noted to feel cool to the touch). This inflammation would extend to the eyes, throat, and tongue, to the point that sufferers “could not bear […] to be otherwise than stark naked.” Thucydides painted a dark picture:

“The bodies of dying men lay one upon another, and half-dead creatures reeled about the streets and gathered round all the fountains in their longing for water. The sacred places also which they had quartered themselves were full of corpses of persons that had died there, just as they were; for the disaster passed all bounds, men, not knowing what was to become of them, because utterly careless of everything, whether sacred or profane”.

By the time the disease finally burned out, an estimated 77,000 to 100,000 people had perished. Survivors were often left with missing fingers and toes, as well as loss of sight due to the disease.

In addition to taking the lives and health of many Athenians, the plague also took a a social and political toll. Many of the upper class died, leaving their money to the hands of the lower class. There was also a drop in citizens able to fight in the wars, leading to the decline of Athens as a superpower of the ancient world.

Theories range as to the cause of this ancient epidemic, especially since its ancient context makes it difficult to retrieve forensic evidence. Popular contenders are bubonic plague, typhus, measles, smallpox, and even hemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola (it was known to have originated in African ports). In 1999, the University of Maryland hosted a medical conference in which it was agreed that the most likely culprit was typhoid, based on current knowledge and contemporary accounts. A 2005 analysis of remains from an Athenian plague pit revealed the bacteria Salmonella enterica, which causes typhoid. However, the pit had also been contaminated by hogs (known carriers of salmonella) around the same time period.

Of all the epidemics covered in this series, the Plague of Athens is the farthest-removed from us by time, scientific advancements and, for some of us, even geography. But the lives it took and its impact on society is no less important for its distance.

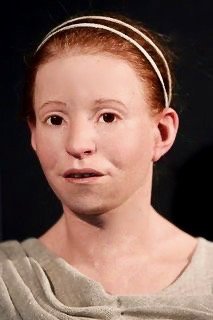

In the 1990s, excavations of a plague pit revealed skeletal remains of an 11-year-old girl lost to the disease. Scientists recreated her facial features and gave her the name Myrtis. In 2010, she was named a Friend of the United Nations, and “wrote” a letter as part of their world campaign to end poverty:

“My death was inevitable. In the 5th century BC we had neither the knowledge nor the means to fight deadly illnesses. However, you, the people of the 21st century, have no excuse. You possess all the necessary means and resources to save the lives of millions of people. To save the lives of millions of children like me who are dying of preventable and curable diseases [….] Listen to me. I know what I’m saying. Never forget that I’m much older and therefore much wiser than you.”