In the second episode of our limited Series “Quarantea”, we learn about the fabled Black Death. We hear even more dramatic reading from Allison, her death plushies make yet another appearance, and Hannah describes in vivid detail how this horrible disease took hold, all while we debate whether fleas can cough.

Listen on Buzzsprout here!

The story of the Black Death is a complicated one that likely began somewhere in China with the bite of a flea on an infected rat. By the mid-1340s, rumors were circulating of a pestilence blazing through India, Persia, Syria, and Egypt, leaving death in its wake. And it was on its way to Europe.

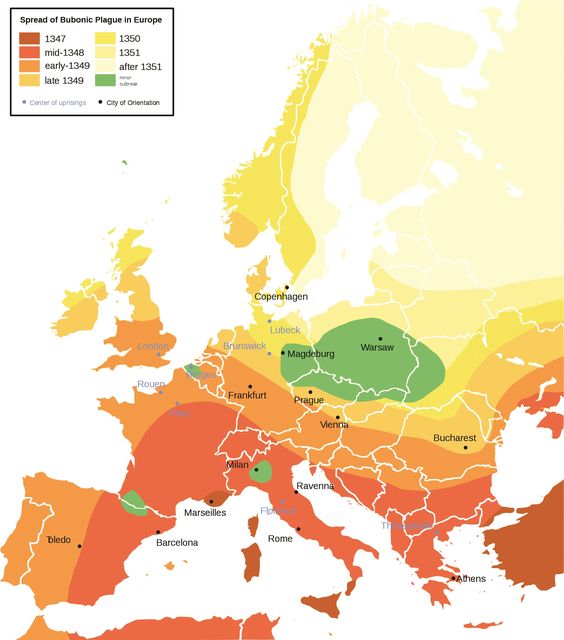

The plague arrived in Europe in October 1347, when 12 ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. Most of the sailors were dead and the ones who were alive were succumbing to a terrifying disease. They were quickly forced by the authorities to leave, but it wasn’t soon enough.

From that port in Messina, the plague made its way through the continent. Just like today, it arrived first in port towns like Marseilles in France and Tunis in North Africa. It wreaked a special kind of havoc in Florence and Rome, the densely-populated hubs of massive trade routes. They were seeing lots of traffic due to recent developments (Marco Polo had completed his legendary journeys just over 50 years prior). By the middle of 1348, plague had reached Paris, Bordeaux, and London.

As the disease raged, Welsh poet Ieuan Gethin described the black sores (referred to as “buboes”), which he saw first-hand in 1349:

“We see death coming into our midst like black smoke, a plague which cuts off the young, a rootless phantom which has no mercy for fair countenance[…] It is of the form of an apple, like the head of an onion, a small boil that spares no-one. Great is its seething, like a burning cinder, a grievous thing of ashy color…They are similar to the seeds of the black peas, broken fragments of brittle sea-coal…cinders of the peelings of the cockle weed, a mixed multitude, a black plague like half pence, like berries[…]“

In England, Henry Knighton referenced the plague’s speed and steady march from East to West:

“Few kept their beds more than two or three days, or even half a day. Then this cruel death spread everywhere around, following the course of the sun.”

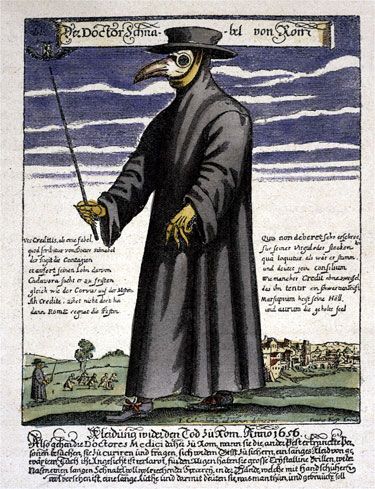

The plague was merciless, leaving physicians of the time unable to offer any effective remedy. Death tolls varied by location, but estimates place it at about 1/3 of the world’s population. In some communities, fatality was 100%, the villages left to be reclaimed by nature. In Florence, the death toll was so great that the burial process had to be adapted:

“At every church they dug deep pits down to the water level; and thus those who were poor who died during the night were bundled up quickly and thrown into the pit; they then took some earth and shoveled it down on top of them; and later others were placed on top of them and then another layer of earth, just as one makes lasagna with layers of pasta and cheese.” (Marchione di Coppo Stefani, eyewitness of the plague in 1348)

Survivors, and those who hadn’t yet fallen sick, were left to respond to the trauma as they would. Some blamed minorities for the disease, others moved into the homes of wealthy victims of the plague and tried to live as much of the high life as they could. Others, known as the flagellants, could only believe this was a judgement from God and roamed from town to town, whipping themselves in an attempt to take the punishment upon themselves.

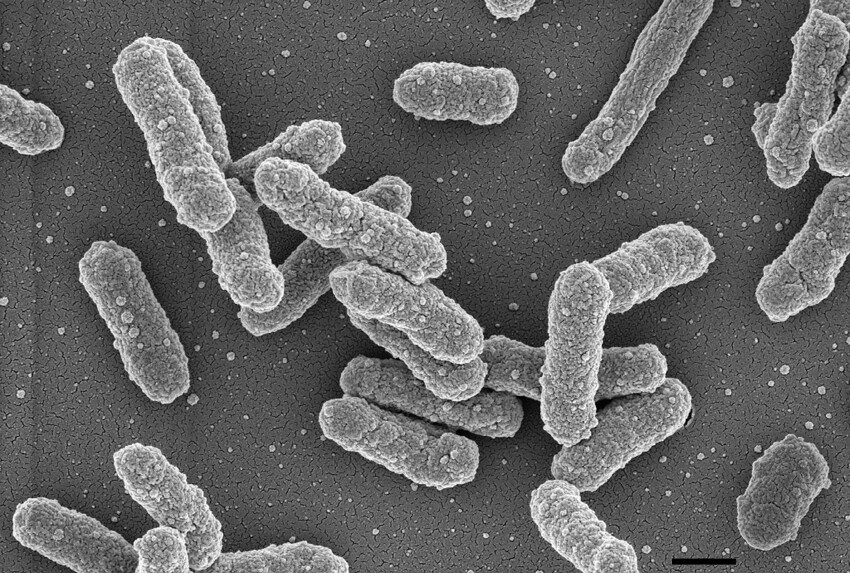

While this wave of the disease eventually burned itself out around 1351, Europe would suffer further outbreaks well into the 1600s. It wasn’t until an outbreak in Hong Kong in 1894 that a doctor named Alexandre Yersin would finally identify the bacteria responsible for the bubonic plague. It was dubbed Yersinia pestis in his honor.

Despite many matches between descriptions in historic records and modern outbreaks, as well as evidence of ancient Y. pestis DNA in many plague graves, some researchers express doubts as to whether bubonic plague was the only or even primary cause of the 1347-51 epidemic. One key discrepancy is transmission rate: it is typically spread by fleas, which feed upon infected rats and then cough the bacteria back into the bloodstream of the next human they bite. Some hold that this process could not have carried the plague fast enough to be the culprit. Other discrepancies include a climate that was too cold for the black rat and the absence of the evidence of the massive rodent die-off that typically precedes modern plague outbreaks.

However, other researchers point out that Y. pestis causes not only bubonic plague, but also septicemic and pneumonic plague. Septicemic plague happens when the bacteria poisons the blood, and can be spread by contact with bodily fluids. Pneumonic plague results when Y. pestis infiltrates the lungs. It can be spread by coughing, sneezing, and even breathing. The combined transmission of the same bacteria by fleas, contact with fluids, and airborne particles would account for a much faster spread of the disease.

We often think of individuals living in medieval times as having a kind of emotional immunity to death because they were, for lack of a better term, “used to it”. And it can’t be denied that due to things like disease, infant mortality, and childbirth, they did experience it much more frequently than we do today. But accounts of the Black Death show a response to loss that rings achingly familiar across nearly 700 years.

In 1348, Edward III of England sent his daughter on a journey to Castile, where she was to marry the heir to the throne. In France, her retinue was stricken with the plague and Joan died at the age of 14. In his letter informing the king of Castile, Edward writes of the experience:

“No fellow human being could be surprised if we were inwardly desolated by the sting of this bitter grief, for we are humans too.”